Lobo Week 2024

Celebrate Lobo week with our drawing and coloring pages!

simply right-click on the image and save it to your device! Be sure to share your artwork with us on social media.

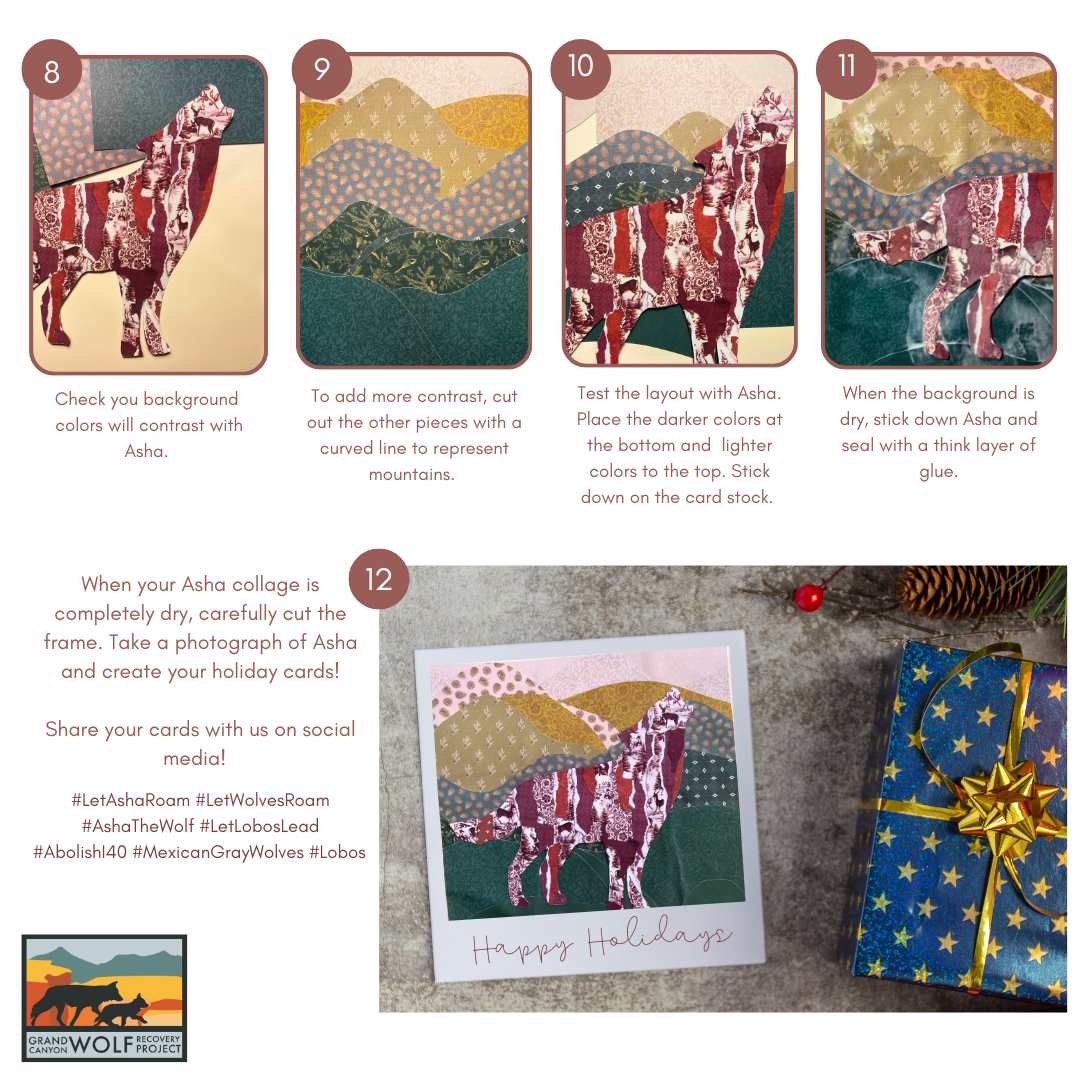

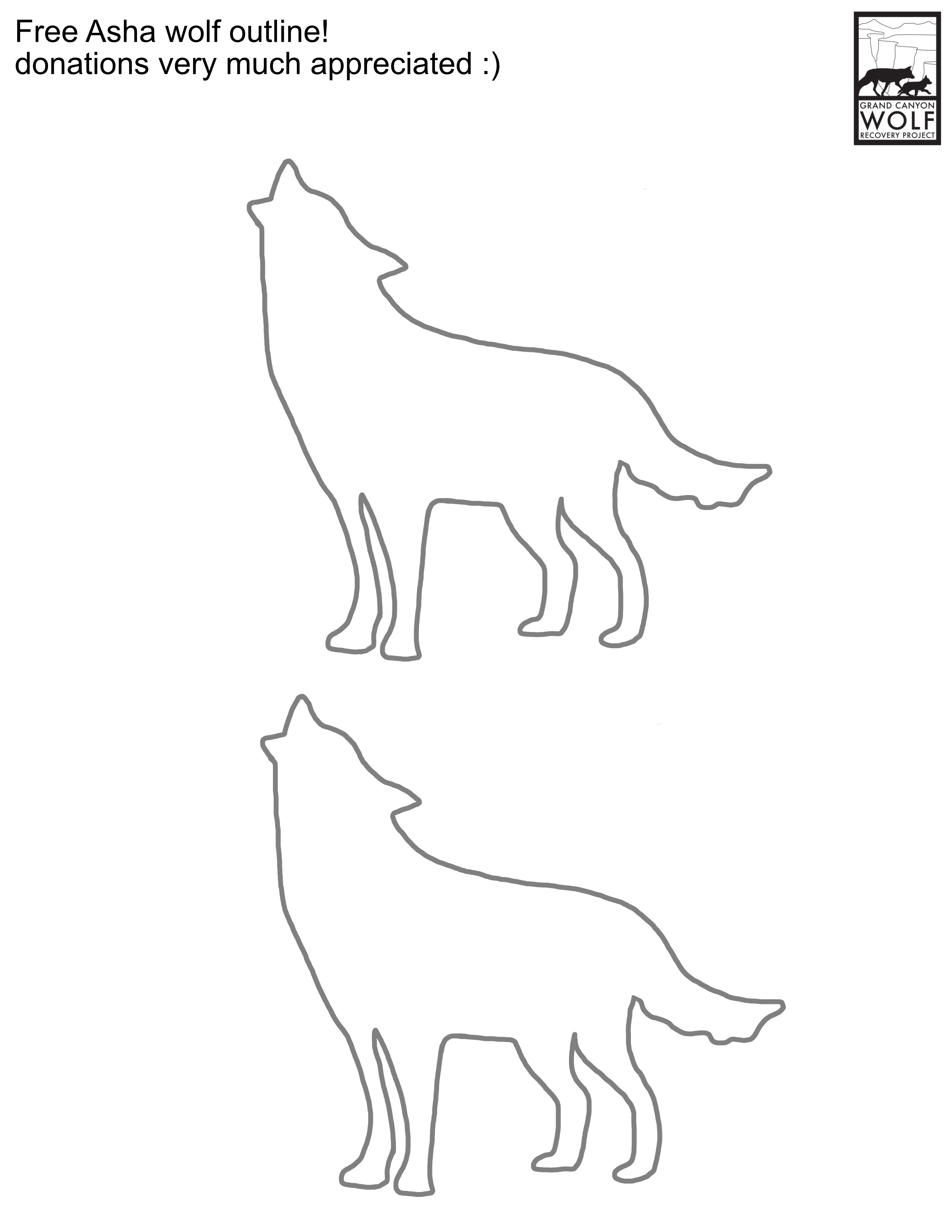

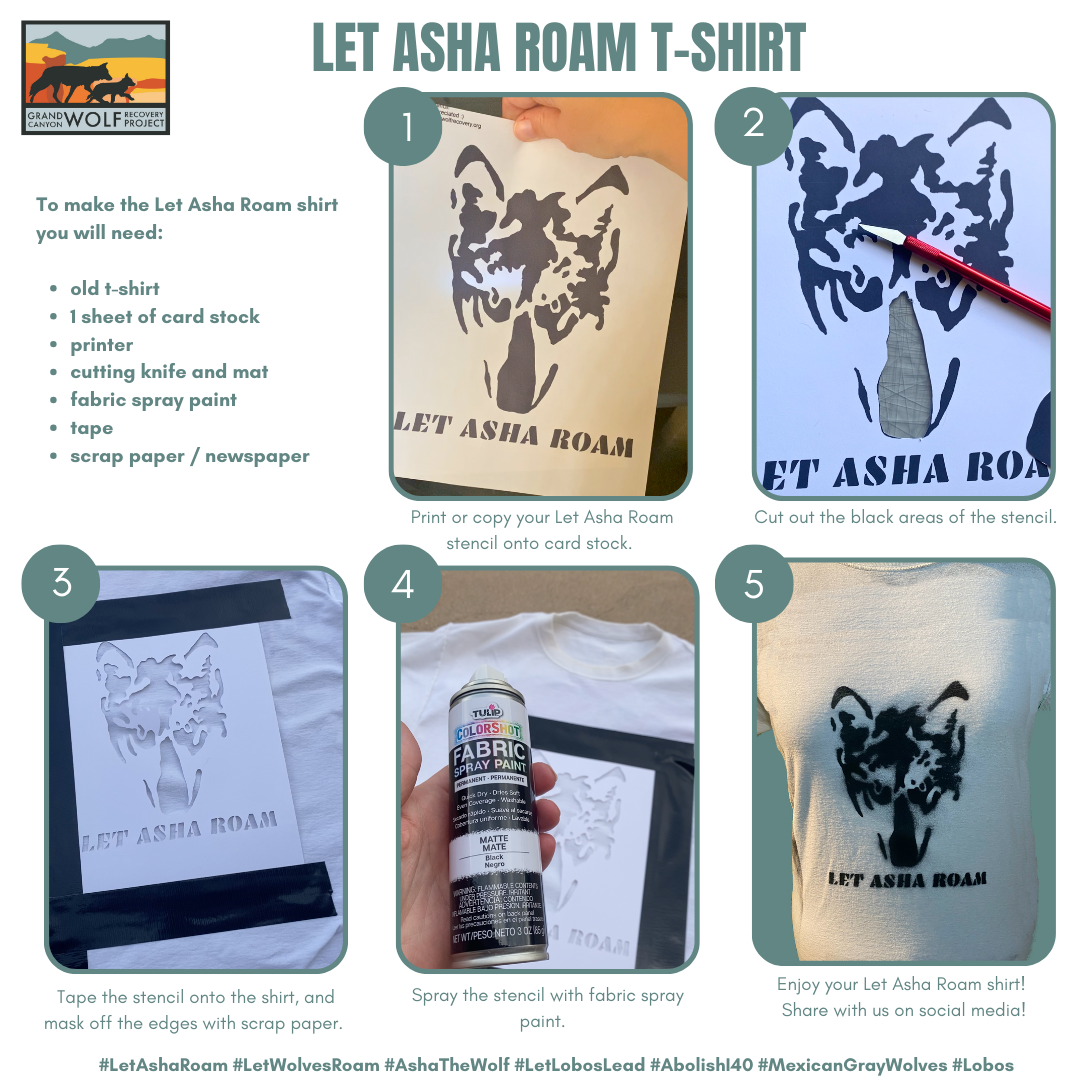

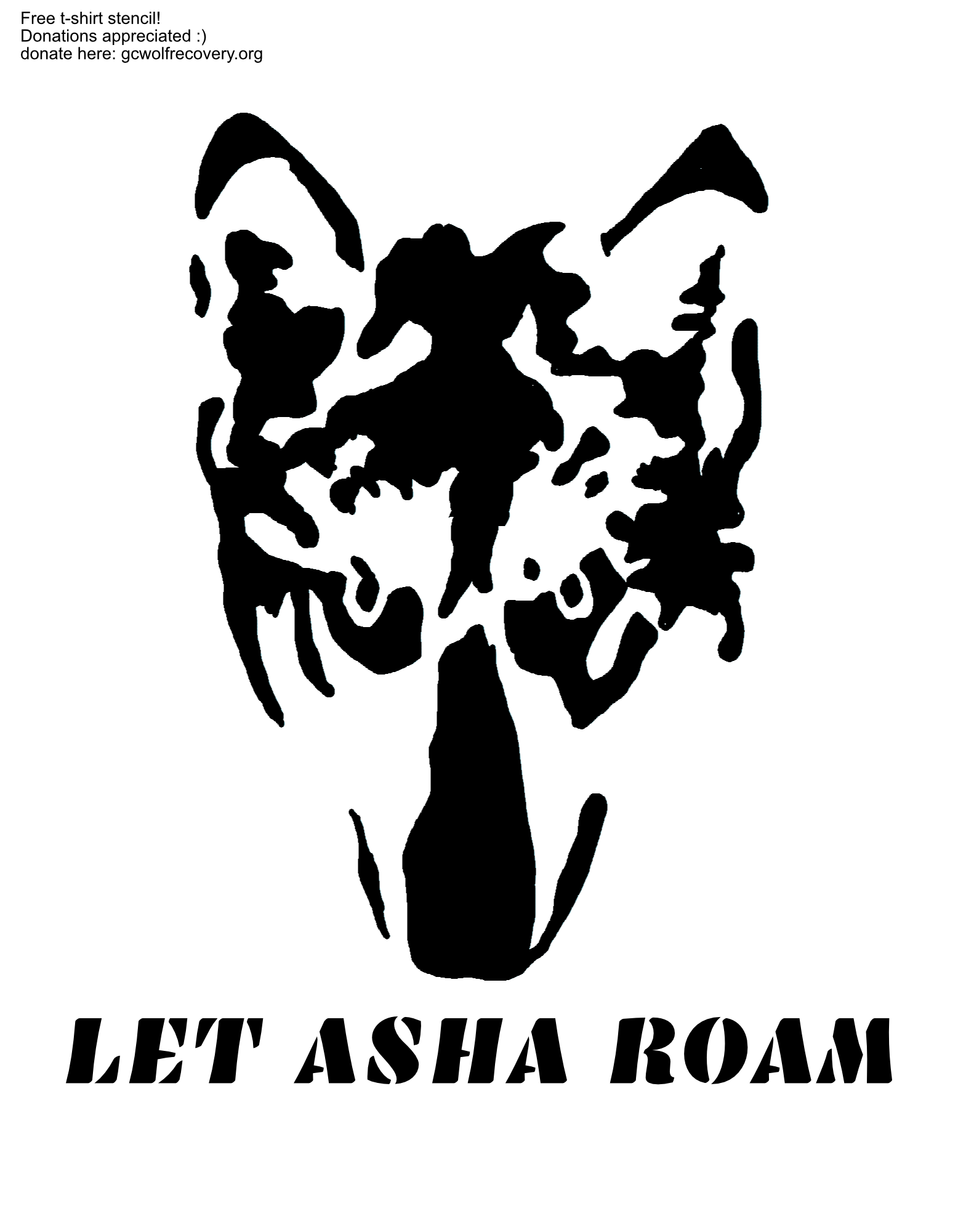

Free instructions and templates for creating your own wolf art pieces!

Want to learn more about Asha? Check out our press releases for current Asha news!

Download your Asha wolf outline by right-clicking on the outline below and saving it to your device.

Right-click on the outline below and save to your device.

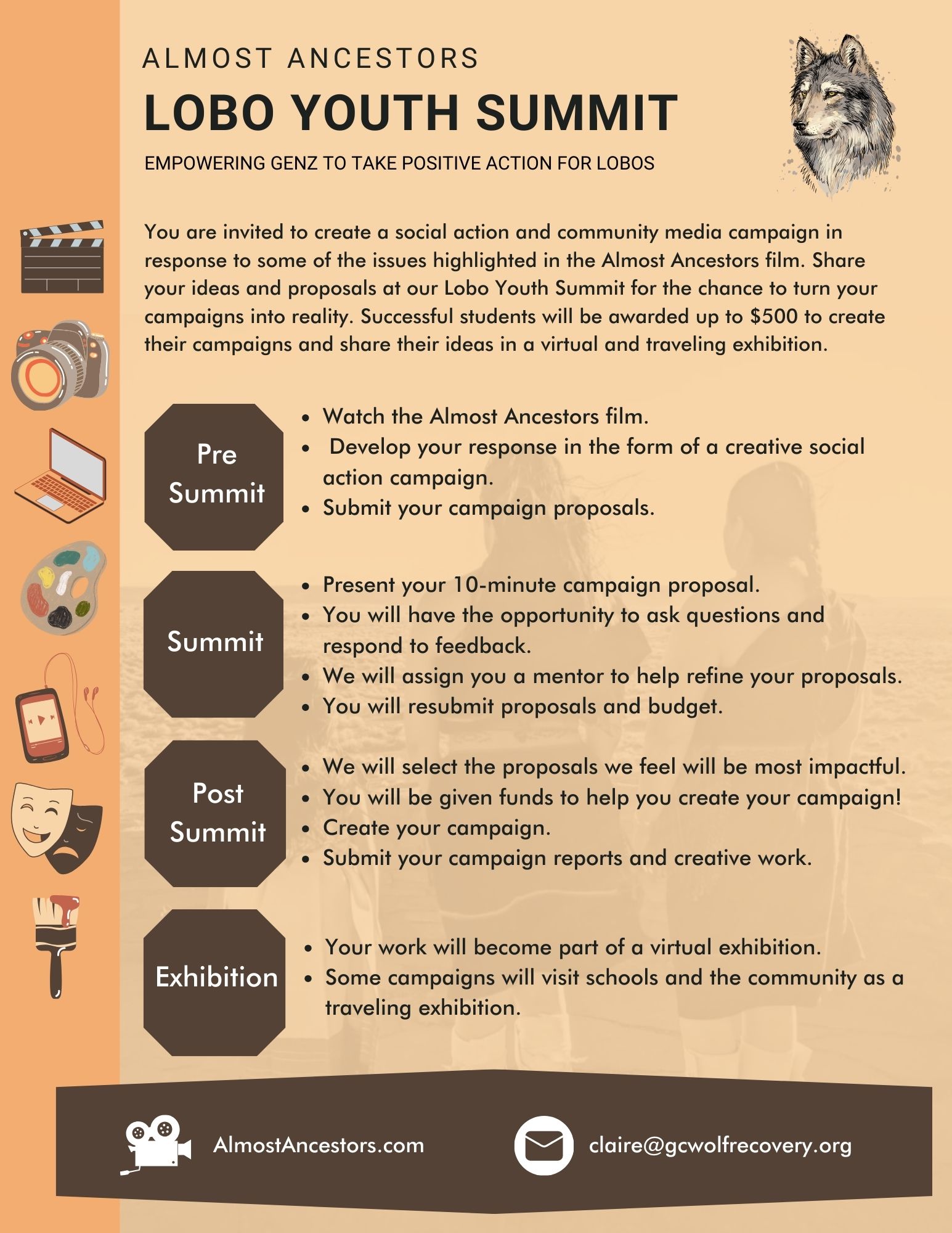

Target audience: Gen Z students between ages17-21. We believe in inclusivity and student groups can be of mixed ages, but we require at least one student to be between ages 17 and 21.

Aim: Students will create a social action and community media campaigns in response to some of the issues highlighted in the Almost Ancestors film.

Key Dates:

*******Lobo Youth Summit Proposal Form is available here now! *******

*******The Lobo Youth Summit Student Guide is available here now! *******

The Lobo Youth Summit is inspired by the award-winning short film Almost Ancestors.

The youth are our future, and we want to help them become confident, informed, and assertive advocates for lobos. Gen Z is emerging as the Sustainability Generation. They care about environmental issues and make decisions based on values and principles. This program taps into the innovative spirit of Gen Z, harnessing their ability to access information, collaborate, and mobilize action. The Lobo Youth Summit invites students to become solutionist thinkers, creating well-researched and impactful social action campaigns for lobos. We already received inspiring responses from students like Samantha and Vinesh, showcasing the potential of this program to shape the future of Mexican gray wolf recovery.

"Being an amateur wildlife photographer and loving nature, I know that by restoring the wolf population and making sure they are healthy, we will be able to restore an ecological balance that was taken away; and the opportunities to experience a fuller natural landscape is something I believe is truly impactful to my life." - Vinesh, BASIS Mesa Junior

"My greatest desire in life is to have a world where everyone can coexist peacefully, both with each other and with nature. As I learn more about the cultural importance of tending to the Earth, I feel more strongly that we all have a responsibility to do so, both to the land and the people living here. That is why the Lobos project matters to me." - Samantha, BASIS Mesa Senior

How it works

With only 286 lobos in the wild in Arizona and New Mexico, lobos need protection. The number one killer of lobos is illegal poaching. We need to expand their boundaries and improve their genetics for the species to survive.

High school and college-age students are invited to create social action and community media campaigns in response to some of the issues highlighted in the Almost Ancestors film.

They will present their ideas at a student summit where they will have the opportunity for feedback and to reflect on other presentations. Successful students will receive up to $500 to turn their ideas into reality. These campaigns will be part of both a virtual and in-person exhibition.

If you are a student or teacher interested in taking part, please register for updates here

The Lobo Youth Summit Creator and Project Leader

The idea of the Lobo Youth Summit was conceived by Claire Musser, Executive Director of the Grand Canyon Wolf Recovery Project, with over 18 years of teaching experience across the UK, the Cayman Islands, and the USA.

Claire Musser is the Executive Director of the Grand Canyon Wolf Recovery Project. She has a Bachelor of Arts in Graphic Design, a Postgraduate Certificate in Education, and a Master of Arts in Anthrozoology, where her research explored Mexican gray wolf recovery from the perspective of the individual wolves. With over 18 years of teaching experience across the UK, Cayman Islands, and the USA, Claire uses her creativity to blend the arts and sciences. As a transdisciplinary teacher, Claire creates meaningful interactive learning experiences linked to real-world problems. As a certified environmental educator, she has presented at educational conferences and published articles about the benefits of using STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and math) to create meaningful educational experiences. She encourages her students to be solutionist thinkers, empowering them to take positive actions in conservation. Claire is a lifelong learner and also a Ph.D. student. Her current research focuses on multispecies entanglements, where she combines photography and anthrozoology to explore human-wildlife conflict and coexistence.

Teacher and Student Testimonials

"As a university student studying global change and environmental management, I'm extremely excited by this project. As issues like climate change and all the contributing factors that affect these overwhelming threats to our planet and various lives continue to grow in severity, we must look towards future generations to help guide us to better, more innovative solutions if we want to achieve long-lasting environmental change. We can only hope to make a real difference by empowering more students to take our futures into our own hands before it's too late. Often, I think people don't realize how much weight their ideas hold. This project is an amazing opportunity to show youths the real-world impact they can have in becoming a force for positive change. By participating in this project, my generation can take those first steps to discover what they can do to truly change the world as individuals and as part of their community. I'm looking forward to seeing these students' passion and drive to save our planet as they come up with new and innovative initiatives to preserve our world for generations to come!" Sidney, student at the University of Arizona

“Growing up on a family farm has allowed me to see the impact that every animal has had on the local environment. I hope to see the massive positive impact that reintroduction of lobos will have on the environment.” - Jacob, BASIS Mesa Junior

“Since I was raised in a developing community, I have seen firsthand the effect that humans have on the animals in our environment. I have witnessed the local coyote population be pushed out of their native ecosystem and disappear completely. This initiative would allow me to make sure that in the future, more animals will be able to live safely in their home, and it will allow me to develop the leadership skills necessary to do so further into the future.” - Joaquin, BASIS Mesa Junior

“The Lobos Project allows for me and my fellow students to learn how to advocate for the environment and inspire others to work towards a healthier world.” - Bird, BASIS Mesa Sophomore

“I’ve always been fond of wolves. I even took a vertebrate zoology course, which expanded my understanding of them and other animals too, and to see lobos, a species so close to home, be on the verge of extinction, knowing I can make a change, motivates me to take action and help them.” - Ashwyn, BASIS Mesa Junior

"I love the idea, and I think it is something that we, and most high schools, would definitely have a population of students interested in... It would be really cool to have a school put on a film festival-type event/gallery with submissions on display." Science Teacher, Scottsdale Unified School District

"This is exactly the kinds of activities we envision students getting involved with." Science Teacher, BASIS Charter Schools

Event Sponsorship

We, and the schools, need your support to create a successful Summit.

If you would like to become an event sponsor, please visit the Almost Ancestors website

if you would like to sponsor a student social action project, please register your area of interest here.

GCWRP is partnering with Project GRIPH (Guarding the Respective Interests of Predators and Humans) to offer a unique opportunity to gain skills and experience in non-lethal methods. You will gain fieldwork experience with wolves and help dispel myths about coexisting with large carnivores.

Project GRIPH specializes in non-lethal wildlife conflict mitigation to help foster equilibrium between rural communities and our wildlife neighbors. Help build a bridge with connection, compassion, and communication between rural and urban America. By joining our expedition, you are helping create a positive reason for rural America to have wolves on the landscape.

Cost per person: $2,700 USD (includes all meals, lodging, wages for staff, rancher fees, and local travel during the program)

We are currently seeking grant funding for upcoming student expeditions, but if you're able to self-fund or organize a group trip, we’d love to work with you—please reach out to explore availability.

Duration: 5 days/4 nights

Group Size: Min group size 4, max group size 5

Available Dates: May or September

Location: GRIPH Ranch, near Colville, Washington State, USA.

A shuttle from Spokane Airport is included. Flights are not included.

Itinerary:

Pre-trip: Before the meeting, immerse yourself in the world of wildlife conservation with the award-winning film Range Rider and the Emmy award-winning PBS documentary about Project GRIPH. In our first virtual one-hour meeting, we delve deeper into the expedition; we will also explore the fascinating world of wildlife careers and pathways into conservation. In our second one-hour meeting, we will guide you in preparing for the expedition, including what to bring for this unique learning experience.

Day 1: Our journey commences with an orientation, where you’ll have the opportunity to meet the horses and gain insights into our mission. This day is designed to assess your comfort level on horseback, familiarize you with backcountry safety, and outline the plan for the upcoming days. We’ll also demonstrate how to apply non-lethal wildlife conflict mitigation techniques practically. We’ll then meet the rancher and delve into the social complexities of wolves returning to the range. The day concludes with an immersive experience in the wilderness, where we’ll howl for wolves and camp overnight on the range.

Day 2: Travel by horseback* and participate in our wolf and cattle behavior workshops. We will learn more about co-thriving with predators as we move cattle on the range. Then, to end the day in the wilderness, we will camp overnight on the range.

Day 3: We travel by horseback and learn about wolf and animal tracking. We end the day in the wilderness by camping overnight on the range. Around the campfire, we will have time to reflect on the activities, discuss our complex relationship with predators, and discuss careers in wildlife conservation.

Day 4: Use your new horseback riding and tracking skills to become a range rider for the day. With plenty of opportunities for wildlife photography, you will also help with trail camera maintenance as we monitor cattle and predators on the range.

Day 5: End the expedition with a debrief and return to Spokane.

Post-trip: We will send you a tailored reference letter about your time on the expedition, including images from the trail cameras we monitored during the workshops.

*We can adjust the horseback riding based on your comfort level, including the option to take part on foot.

Want to make a lasting impact on wildlife conservation and help shape the future of coexistence and co-thriving?

We’re actively seeking partners and supporters to help fund the next Pathways to Conservation expedition. Your support will directly provide scholarships, travel, meals, and mentorship for students, especially those from underrepresented communities, who are ready to lead the way in building a more compassionate, science-informed approach to carnivore conservation.

🟢 Interested in funding an expedition or sponsoring a student?

Please reach out to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. — we’d love to collaborate with you.

🟢 Are you a student who wants to join us on the range?

If you're passionate about wildlife, justice, and reimagining human-animal relationships—and want to be considered for a future expedition—we want to hear from you.

Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. with a brief statement about your interest, background, and what you hope to gain from the experience.

Our next expeditions are tentatively scheduled for May and September 2026, depending on funding availability. Whether you’re ready to get in the saddle or ready to make it possible for others, you’re part of the future we need.

Together, let’s co-thrive.

Additional Information:

Daniel Curry is a range rider, speaker, and founder of GRIPH + Project GRIPH, organizations dedicated to helping humans co-thrive with large carnivores through conservation, connection, and education.

After working with wolves for a decade in sanctuaries and zoos across the United States, Daniel spent the next ten years developing non-lethal methods that continue to help people and wolves co-thrive together.

Daniel’s work helps guard the respective interests of predators and humans, building a bridge between animals and people in Washington state. His work has been featured in the film Ranger Rider (Wild Confluence Media), and in publications around the world.

“As wolves repopulate Washington State, conflict is heating up with rural ranching communities. Range rider Daniel Curry’s job is to patrol wild areas on horseback, creating a buffer between wolves and the cattle herds that graze on public lands.”

“Daniel Curry spends his days on horseback studying wolves’ migration patterns and deterring them from encroaching on the human landscape while educating and partnering with local ranchers on non-lethal methods of wolf prevention.”

A cattle rancher and a wolf-protecting cowboy unite to preserve what’s dearest to them.

Last month, three NAU “Women in Wildlife” students and volunteers from the Grand Canyon Wolf Recovery Project returned from a weeklong grant funded expedition in northeastern Washington with Project GRIPH (Guarding the Respective Interests of Predators and Humans), an experience that challenged their perceptions, expanded their field skills, and deepened their commitment to wildlife conservation.

The expedition, part of the new Pathways to Conservation program, immersed students in the daily reality of range riding: a non-lethal strategy for reducing conflict between large carnivores and livestock. Guided by Project GRIPH founder and range rider Daniel Curry, fourth-generation rancher Jerry Francis, the team learned to read wolf tracks, walk calmly past cattle to minimize stress, deploy trail cameras, and monitor predator behavior, all while engaging in difficult conversations about coexistence and co-thriving on multi-use landscapes.

Hosted in the heart of Washington’s wolf country, the program offered more than technical training. It invited students to step into the complex social and ecological relationships that shape wolf recovery in the Western United States. As the only programs in the U.S. focused on co-thriving—not just coexisting—with carnivores, Pathways to Conservation equips future conservationists with both practical tools and ethical frameworks to navigate a divided landscape.

“Jerry's willingness to share his stories with us taught me how much trust and relationship-building matter in this work. His generational connection to the land and firsthand understanding of wildlife patterns showed me that ranchers aren't obstacles to conservation but possible partners with vital local insight. I learned that conservation is actually about expanding our definition of community to include both human and non-human neighbors.” Mackenzie Buckley

“Meeting Jerry and being on the landscape up in Washington provided us with the unique opportunity to see what living with large carnivores really looks like. After seeing just how closely Jerry lives with these animals, we can try to figure out the best ways for others to coexist and co-thrive.” Sophie Norris

Beyond the field, students also attended the Seattle Film Festival for the premiere of Wolf Land, a new PBS documentary featuring Daniel Curry’s work. The film sparked passionate dialogue about how stories shape public understanding of wolves.

“Wolf Land was a powerful and inspirational film that did an excellent job demonstrating how range riding is an effective solution. Not only did it show the impacts of range riding, but a key element that stuck with me was the trust between rancher and rider. Jerry and Daniel have a special relationship where they work together for both the good of the rancher and the wildlife.” Justine Koehler

“Wolf Land showed me that the conflict doesn't have to be a zero-sum game. Seeing Daniel Curry's work in action gave me hope—the film beautifully illustrated genuine experiences of deterring wolves from private lands where ranchers might otherwise resort to lethal control. There are real, practical solutions out there.” Mackenzie Buckley

With guidance from both Project GRIPH and GCWRP, these students will now develop a public presentation for the Big Lake Holiday Campout, co-create educational materials, and share their fieldwork experiences at the upcoming Lobo Youth Summit and beyond. Their voices are already shaping a new generation of wolf advocacy rooted in compassion, science, and storytelling.

“It was incredible to have this opportunity to learn so much about range riding, the ranchers, and wildlife from Daniel. His work is proof that coexistence and co-thriving are possible and attainable. Experiencing these methods of human-wildlife conflict mitigation firsthand helped evolve my perspectives on the hard work these ranchers put in, the interpersonal relationships between range rider and rancher, and the wildlife. I will use the knowledge I learned on this trip for all of my future years in wildlife conservation.” Justine Koehler

This pilot project marks the beginning of a growing partnership between Project GRIPH and GCWRP. Together, we aim to expand hands-on wildlife programs that are accessible to students from all backgrounds.

"I had the privilege of co-hosting our first collaborative empowering women in wildlife program—Pathways to Conservation with Claire Musser from the GCWRP.

It was an honor to be able to offer this opportunity to these three inspiring women, Justine, Mackenzie, and Sophie.

I believe that women offer a much needed perspective that is lacking in the arena of wildlife work. In my experience, women tend to approach the highly complex matters of wildlife management with a higher level of compassion and understanding for all parties involved. I believe in our current time and climate, both political and literal, we need to empower women to take the mantles that have been typically held by men. We have seen the consequences of having a male-dominated system govern our natural world. I would like to see more opportunities for women to showcase their compassion and empathy for this special planet and all of its inhabitants.

Sophie, Mackenzie, and Justine exemplify what we are lacking in Wildlife management. I look forward to the day when it is commonplace to see women of this caliber working in the field of wildlife. I truly believe that if we shed the archaic mindset that patriarchal-centric systems are better than a more balanced system, including the critically lacking perspectives of women, we will see the positive repercussions for generations to come. It will take brave women like Mackenzie, Sophie, and Justine." Daniel Curry

Daniel taught us to look closely—not just at wolves, but at the relationships that shape the landscape. Now, these students are carrying that vision forward, building bridges where others see conflict. Learn more about Daniel’s work and meet him in person at the Big Lake Howliday Campout this August, where he’ll join us as a special guest to share stories, strategies, and inspiration from the field.

Welcome to Willow's Den

Greetings from our Mexican Gray Wolf Ambassador!

Willow has been an ambassador for their wild Mexican gray wolf relatives with the Grand Canyon Wolf Recovery Project for many years. Willow recently received their name during a naming contest for children from all over the world. The winning name was submitted by a 9-year-old named Sylvia who is in 3rd grade. When asked why she chose this name and why she likes wolves, she stated, "The name will remind people of nature and the importance of wolves to the environment. They are part of a healthy and balanced planet."

Within the Grand Canyon Ecoregion, there is a species of willow named Salix arizonica (Arizona willow). This subalpine species is found near wet meadows, streamsides, and cienegas in Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado. Willows are often overgrazed by ungulates (hooved mammals). Willows benefit from the presence of wolves because wolves help to keep ungulate species moving, therefore they can't overbrowse the willows in sensitive riparian areas.

Mexican gray wolves are one of the rarest and most endangered animals in North America. All Mexican gray wolves alive today are the descendants of just seven individuals that were left by the early 1980s. Thanks to the efforts of captive breeding facilities around the U.S. and Mexico, Mexican gray wolves were saved from extinction and reintroduced back into the wild on March 29, 1998. As of the last U.S. population count at the end of 2021, only 196 Mexican gray wolves exist in Arizona and New Mexico. They still face many threats for their long-term recovery and conservation in the wild, including limited genetic diversity and artificial boundary rules that hinder their ability to disperse into the excellent habitat of the Grand Canyon region.

The Grand Canyon Wolf Recovery Project believes that building public respect and support for Mexican gray wolves throughout their current and future habitat is essential to their successful long-term recovery. You’ll see Willow at community events in Flagstaff and around the Grand Canyon region. As our Mexican gray wolf Ambassador, Willow has an important role in helping us reach hearts and minds about the benefits of restoring wolves in the Grand Canyon region.

Two of Willow's favorite books to recommend for young readers are titled "Wolf Babies!" by award-winning husband-and-wife photography team Lisa and Mike Husar and "Howl: A New Look at the Big Bad Wolf" graphic novel by artist and author Ted Rechlin. Both of these books as well as stickers of adorable Willow are available for sale in our Lobo Marketplace.

Willow, the Wolf ambassador, illustrations were created for the Grand Canyon Wolf Recovery Project by artist Licia Baldini. You can follow Licia's work on social media @artegreen.it. You can create your own recycled 3D craft project of Willow at home by watching the video below and following this link to the Arte Green blog post with templates you can print out. The Arte Green site is in Italian, so be sure to use your browser to translate the directions to English or the language of your choice.

Download and print the templates for 3D Willow craft project in the YouTube video

You may also download coloring sheets of Willow and their family to print out and color at home.

Willow coloring page

Willow howling coloring page

Willow with family coloring page

Follow Willow's adventures on TikTok!

@gcwolfrecovery_

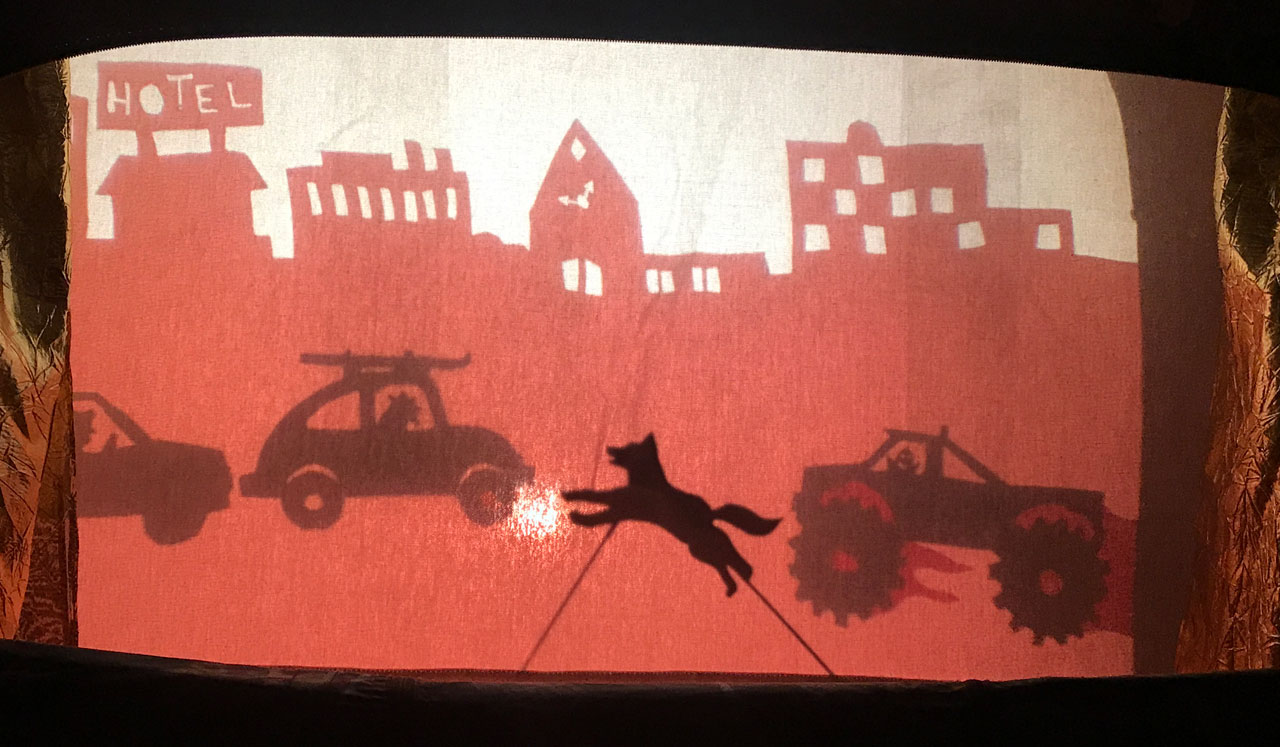

Follow the Water is a (prerecorded, because pandemic :/) puppet show about the struggle of wolves to have a place in nature and in our hearts. It's a story to demistify what it means to live a wolf's life and to turn the tables on how humans view wolves' role in the ecosystem. We are taught through many classical stories and metaphors that wolves are dark creatures, that they are to be feared, despised, and sadly, exterminated. This story brings to life the endearing and social qualities of wolves that are not so unlike ourselves and shows how the reintroduction of wolves to wild places may reverse the collapse of other threatened species and even entire ecosystems. Follow the Water begs the question- What happens when we suppress our own wildness? And what is possible if we don't?

The story follows the adventures of a young dispersing wolf and the friendly wild creatures it meets along the way. What do a frog, beaver, elk and condor have in common with a wolf? What happens when wolves and humans collide? Where will this young wolf end up? Woven together through projector shadow puppetry, hand puppets, and marionettes we go into the unknown with the young wolf. Both positive and interactive, this show is sure to get elders and youth singing and clapping along.

Fill out this short request form for free access to the full 27 minute video for playing for your classroom or group.

Adopt A Puppet! Contact us if you would like to contribute to this project.

Special Thanks to the National Wolfwatcher Coalition for an education grant to support our puppet show!

The Wolf and the Elk: A Play by the FunTown Circus Camp in Flagstaff, AZ.

A Play written by Katie Nelson and directed by Katie Nelson and Garrison Garcia. Performed by the participants of the FunTown Circus Camp in at The Orpheum Theater in Flagstaff, AZ on August 7, 2015. Video by N. Renn.

A PSA video created for the Grand Canyon Wolf Recovery Project by students in the Northern Arizona University Environmental Science & Studies Senior Capstone class for their Change the World project, Spring 2015. Created by Alysse Lerager, Rachel Heydorn, Christy Harvey, and Brian Jagiello.

Enjoy this video of a drum circle and chant to raise awareness for Mexican wolves and the Grand Canyon Wolf Recovery Project, created, performed, filmed, and edited by the students of the Mount Elden Middle School Animal Society in Flagstaff, AZ, 2013. Thank you MEMS Animal Society for your care for Mexican wolves!

Read poems submitted by Flagstaff Area Students for our Wild & Scenic Film Festival event in 2012 & 2013:

Contact our Education Coordinator at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to discuss education programs and ideas for students to learn about wolves at your school.

What is the current status of wolves in the Southwest?

Are wolves dangerous?

Are wolves destroying the livestock industry?

Are ranchers compensated?

Are wolves having an impact on hunting?

Has the regional economy of the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area in AZ and NM been negatively impacted by the reintroduction of the Mexican wolf?

Can wolves help regional economies?

How do wolves benefit the environment?

Do people in Arizona and New Mexico want wolves?

Why did wolves disappear?

What is the difference between "threatened" and "endangered" status of wolves?

Why do you want to put wolves in the Grand Canyon?

Where is the Grand Canyon Ecoregion?

Would wolves live everywhere throughout the Ecoregion?

Who is involved with the Grand Canyon Wolf Recovery Project?

How can I learn more about wolves in this region?

Do you have educational materials available for teachers?

What can I do to help bring wolves back to the Grand Canyon Ecoregion?

Education & Community Events

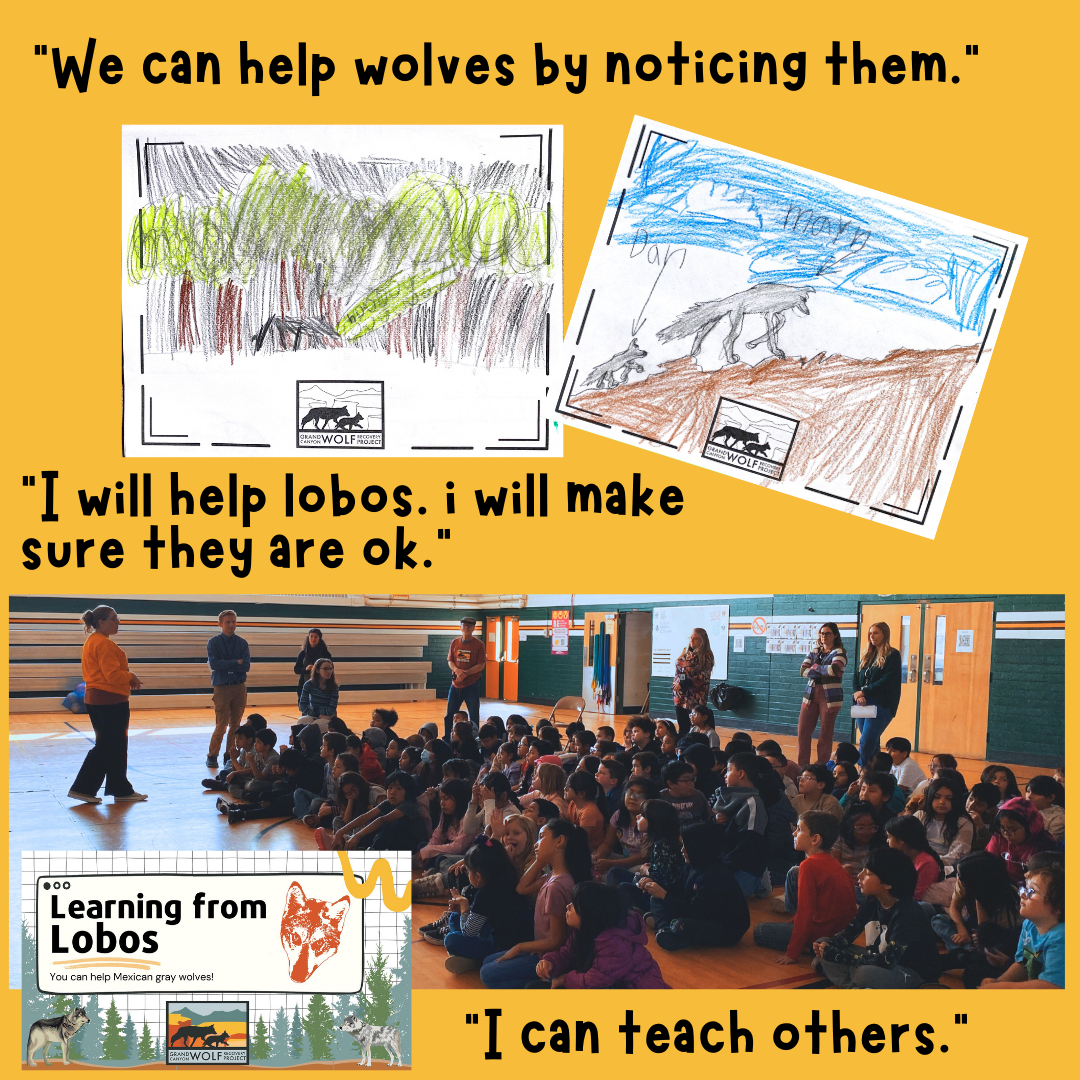

Learn from the wolves with our new Learning from Lobos program! Together, we explore the lives of wolves through our inquiry-based program, which uses storytelling to challenge wolf misconceptions and foster compassion. Participants will learn how we teach critical thinking, empathy, and environmental stewardship through interactive STEAM activities, challenging misconceptions and enhancing connections between humans and wildlife.

We have the following programs available:

Please fill out the information form, and we will contact your given email to arrange your event.

K-12 Teacher Resources

Educating Visitors to the Grand Canyon

Educating Visitors to the Grand Canyon

With the help of our dedicated volunteers, the Grand Canyon Wolf Recovery Project hosts our “Howl for Wolves” at the Grand Canyon Outreach Campaign each summer in Grand Canyon National Park.

We have successfully educated over 6,000 people from the U.S. and abroad about wolves by tabling at the North and South rims during the months of June, July, and August each year.

Our tabling campaign has generated over 3,000 post cards to Benjamin Tuggle, former Southwest Regional Director of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS) and over 500 hand-written post cards to former U.S. Secretary of the Interior, Ken Salazar expressing support for the recovery of wolves to the Grand Canyon region.

This very successful project was developed with three goals in mind:

1. Disseminate information to visitors from the U.S. and abroad about the historical role wolves played in this vicinity, their current status in the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area, and the potential for future inhabitation throughout this region.

2. Dispel myths about wolves and teach the public about wolf behaviors, pack structure, hunting habits, and the biological niche wolves fill in healthy ecosystems, using the success in Yellowstone to illustrate the way an ecosystem will begin to heal itself when a top predator is reintroduced.

3. Engage with a supportive public, encouraging them to write agency officials to show the widespread support for wolf recovery in the Grand Canyon Ecoregion, as well as build a strong pro-wolf constituency to aid us in our campaign to bring wolves back to the Grand Canyon Ecoregion.

The Mexican gray wolf (Canis lupus baileyi) is the most genetically distinct subspecies of gray wolf in North America, as well as the smallest in size. A typical Mexican wolf is about 4.5- 5.5 feet long, from snout to tail, weighs from 50 to 80 pounds, and has a coat with a mix of buff, gray, red and black. Like all wolves, the Mexican wolf communicates using body language, scent marking and vocalization. The main prey for Mexican wolves is elk making up 74% of their diet. Other prey species include white-tailed deer, mule deer, javelina, jack rabbit, cottontail rabbits and smaller mammals.

Commonly called "lobo", the Mexican gray wolf has all but disappeared from its historic range in the southwestern United States and throughout Mexico. Predatory controls from the late 1800s to the mid-1900s made it the rarest gray wolf in North America. By the late 1970s, the Mexican gray wolf had virtually disappeared in the southwestern United States. It was listed as endangered on the federal endangered species list in 1976. An initial recovery objective of a wild population of at least 100 wolves over 5,000 miles of its historical range were approved by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and the Direccion General de la Fauna Silvestre in Mexico in a 1982 recovery plan. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) considers Mexican wolf recovery the highest priority for wolf conservation worldwide.

In 1997, a plan was approved calling for the reintroduction of Mexican wolves in Arizona and New Mexico. In March 1998, 11 Mexican gray wolves in three family groups were released into the wilds of the Apache National Forest of southeastern Arizona. Two additional wolves were released later that year. The highlight of the recovery program took place in 1998 when, for the first time in 50 years, a Mexican gray wolf pup was born in the wild.

Illegal shooting still remains the number one killer of wolves along the Arizona-New Mexico border having claimed at least 105 wolves from 1998 - 2019. The US Fish & Wildlife Service revised the rules in January 2015 to allow for broader roaming privileges letting the wolves roam outside of the current Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area, which is considered too limited by scientists. This would allow wolves to naturally disperse into other places with suitable habitat throughout the southwest, but they will impose an artificial, and politically-based boundary at Interstate I-40. Wolves are still prohibited from establishing territories in the Grand Canyon region. Conservationists and some ranchers agree that the human-wolf conflict could be eased if wolves weren't so concentrated.

Wolf recovery requires both captive breeding and reintroduction to the wild. Captive management is necessary to increase the population and to minimize the potential for in breeding depression. Reintroduction is essential to ensure that Mexican wolves exist in the wild and persist as more than just a population of zoo wolves. The first captive-reared Mexican wolves were reintroduced into the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area beginning in January 1998. Immediately prior to reintroduction, no wild Mexican wolves were thought to remain in the U.S. or Mexico.

Currently, there are about 196 Mexican wolves roaming free in the wild in the U.S. There are also currently about 380 wolves at 60 captive breeding facilities throughout the United States and Mexico.

To read more about the feasibility of wolves in the Grand Canyon Ecoregion, visit this page.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service's Mexican Gray Wolf Recovery Program

Brown, Wendy. El Lobo Returns. International Wolf; 1998. 8(4): 3-7.

United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Mexican Wolf Recovery Program: Natural History and Recovery Fact Sheet. 1997.

United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Mexican Wolf Recovery Program: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions about the Reintroduction of Mexican Wolves in the Southwest. 1997.

Wildlife Committee of the Rio Grande Chapter of the Sierra Club and the Mexican Wolf Coalition. The Mexican Wolf. Albuquerque, NM: Sierra Club; 1993.

(Most of the information above is from The International Wolf Center website www.wolf.org)

Aldo Leopold, the father of modern wildlife management and author of A Sand County Almanac, admonished wildlife managers to retain all the pieces of our ecosystems (1953). Using modern analysis, present day ecologists are finding Leopold's directive to be right on the mark. Predation and particularly predation by large carnivores is a necessary component of all healthy ecosystems. Study after study has shown that predator loss leads to biodiversity loss (Diamond 1992). Large predator presence is so important, in fact, that conservation biologist John Terborgh (1988) wrote that "Disrupting the balance by persecuting top carnivores, by hunting out peccaries, pacas, and agoutis, or by fragmenting the landscape into patches too small to maintain the whole interlocking system, could lead to a gradual and perhaps irreversible erosion of diversity at all levels - both plant and animal." Recognition of this importance has prompted leading wildlife professional organizations such as The Wildlife Society and The Society for Conservation Biology, to dedicate special issues of their journals expressly to predator ecology and conservation. Moreover, these scientific societies have placed the restoration of predators high on their list of conservation priorities.

Although many quite vigorously contend that every bite a wolf or other predator takes out of a prey species adds to the other mortality factors already impacting prey populations, predator-prey relationships are rarely that simple (Krebs 1997). For example, in the Adirondacks of New York state, a healthy wolf population is expected to take approximately 4,000 white-tailed deer per year (Hosack 1996). But nearly 18,000 deer die each year of starvation during the harsh winters. Does that mean that after wolf reintroduction mortality is going to jump to 22,000 per year? Probably not. A more likely scenario is that mortality will be compensatory rather than additive and the region would experience an equivalent reduction in winter mortality. In simple terms, wolves would kill the animals that are most likely to die anyway instead of killing an additional amount over the normal winter die off.

In addition, wolves and other predators often have indirect effects on prey population dynamics. In Washington state's Olympic National Park, elk reproduction appears to be dampened because herds are dominated by older females who typically have fewer twins. As wolves preferentially prey on older animals (Pimlott et al. 1969), their future presence could actually increase overall reproduction in the herd. Moreover, reduction in adult ungulate numbers has been shown to increase fawn survival (White and Bartmann 1997).

If the biota, in the course of aeons, has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering. --- Aldo Leopold

Some people mistakenly believe that all predators serve the same function. But while coyotes and wolves appear to be very similar, their roles and impacts on ecosystems are very different. Wolves are coursing predators, which means that they tend to chase their prey until they find an animal that is weak. This is very different from the opportunistic way coyotes generally hunt--taking whatever crosses their path. Wolves are also pack hunters who hunt cooperatively and whose populations respond very quickly to increases or decreases in prey availability. Coyotes are more individualistic: hunting in smaller units and responding very quickly to increases in the prey bases and very slowly to decreases due to the adaptability of their hunting skills. As a consequence of their different behaviors, they have different impacts on their prey. Wolves tend to eliminate the old, sick, and genetically inferior animals from populations (Pimlott et al. 1969) and coyotes, like bears and cougars, seem to take animals without regard to their condition (O'Gara et al. 1988).

Likewise, other predators hunt differently and take different animals at different times and under different circumstances. Predator-prey relationships are very complex and have evolved over thousands and thousands of years. As our understanding of the interplay between predators and prey has increased, so has our acknowledgment these relationships should be maintained intact.

In 1988, Michael Soulé, founder of The Society for Conservation Biology, documented the phenomenon known as meso-predator release (Soulé et al. 1988). He found that removal of large predators led to a tremendous increase in smaller predators. When wolves are eliminated coyote populations explode. Likewise, when coyotes are removed, foxes prosper. The overall result is an increase in the impact of predators on prey. To illustrate this last point, consider that wolf expert L. David Mech has estimated that each reintroduced wolf pack (10 wolves) in Yellowstone will displace 50 coyotes. When looked at from a hunter's point of view, it seems clear that 1000 pounds of wolves will require less food than 1750 pounds of coyotes. Since the reintroduction in 1995, there are now 80% less coyotes in the Yellowstone region.

Real life examples of meso-predator release abound. When red wolves disappeared from the Southeast coyotes moved in and raccoons increased. In Mississippi this greatly impacted wild turkey reproduction (Miller et al. 1997). Similarly, removal of coyotes in the prairie pothole region benefited fox populations but lowered duck nest success by 15% (Sovada et al. 1995). Fortunately, two recent studies in the Northern Rockies (Arjo et al. 1997 and Crabtree, unpub.) demonstrate that these trends can be reversed. Both studies indicated that recolonizing and reintroduced wolves are displacing and in some instances killing coyotes. The remaining coyotes are relegated to the margins of occupied wolf habitats and are making dietary shifts back to smaller prey items such as rodents.

Armed with a new understanding of the role of predators, public opinion about predators has shifted dramatically (Brunson et al. 1997). Hopefully, that shift can be translated into predator management, conservation and restoration policies that are driven by the best available science and that strive to maintain appropriate predator assemblages in all natural areas across our nation.

Literature Cited

Arjo, W.M., R.R. Ream, and D. Pletscher. 1997. The effects of wolf colonization on coyote behaviors, movements, and food habits in northwestern Montana. *

Brunson, M., T.A. Messmer, D.G. Hewitt, and D. Reiter. 1997. North American public attitudes toward predators, predation, and predator management. *

Diamond, J. 1992. Must we shoot deer to save nature? Natural History. 2-8.

Hosack, D. 1996. Biological potential for eastern timber wolf re-establishment in Adirondack Park. Wolves of America conference Proceedings. 24-30.

Krebs, C.J. 1997. The role of predation theory in wildlife science and management.*

Leopold, A. 1953. A Sand County Almanac with essays on conservation from Round River. New York: Ballantine Books. 190.

Miller, D.A., L. W. Burger, B. D. Leopold, and G.A. Hurst. 1997. Wild turkey hen survival and cause-specific mortality in Central Mississippi. *

O'Gara, B.W. and R.B. Harris. 1988. Age and condition of deer killed by predators and automobiles. 52:316-320.

Pimlott, D.H., J.A. Shannon, and G.B. Kolenosky. 1969. The ecology of the timber wolf in Algonquin Provincial Park. Can. Dep. Lands For. Res. Branch Res. Report. No. 87.

Soulé, M.E., D.T. Bolger, A.C. Alberts, J. Wright, M. Sorice, and S. Hill. 1988. Reconstructed dynamics of rapid extinctions of chaparral-requiring birds in urban habitat islands. Conservation Biology. 2:75-92.

Sovada, M.A., A.B. Sargeant, J.W. Grier. 1995. Differential Effects of Coyotes and Red Foxes on Duck Nest Success. Journal of Wildlife Management. 59:1-9.

Terborgh, J. 1988. The big things that run the world. Conservation Biology. 2:402-403.

White, G.C. and R.M. Bartmann, 1997. Effect of density reduction on overwinter survival of mule deer fawns. *

*Denotes scientific findings presented at the 1997 Annual Meeting of The Wildlife Society in Snowmass, Colorado. September 21-27.

Wolves are highly intelligent. Their acute hearing and exceptional sense of smell - up to 100 times more sensitive than that of humans - make them well-adapted to their surroundings and to finding food. Some researchers estimate that a wolf can run as fast as 40 miles an hour. Wolves have been known to travel 120 miles in a day, but they usually travel an average of 10 to 15 miles a day. Wolves live, travel, and hunt in packs of four to seven animals, consisting of an alpha, or dominant pair, their pups, and several other subordinate or young animals. The alpha female and male are the pack leaders, tracking and hunting prey, choosing den sites, and establishing the pack's territory. The alpha pair mate in January or February and give birth in spring, after a gestation period of about 65 days. Litters can contain from one to nine pups, but usually consist of around six. Pups have blue eyes at birth and weigh about one pound. Their eyes open when they are about two weeks old, and a week later begin to walk and explore the area around the den. Pups romp and play-fight with each other from a very young age. Scientists think that even these early encounters establish hierarchies that will help determine which members of the litter will grow up to be pack leaders. Wolf pups grow rapidly, reaching 20 pounds at two months and full size in a year. All adults share parental responsibilities for the pups. They feed the pups by regurgitating food for them from the time the pups are about four weeks old until they learn to hunt with the pack.

A wolf pup is the same size as an adult by the time he or she is about a year old, and is able to mate by about two years of age. Pups remain with their parents for at least the first year of their of their lives, while they learn to hunt. During their second year of life, when the parents are raising a new set of pups, young wolves can remain with the pack, or spend periods of time on their own. Frequently, they return in autumn to spend their second winter with the pack. By the time wolves are two years old, however, they leave the pack for good to find mates and territories of their own.

Not all the pups in a litter live to the age of dispersal, of course. Biologists have determined that only one or two of every five pups born live to the age of 10 months, and only about half of those remaining survive to the time when they would leave the pack and find their own mates. Adult wolves on the other hand, have fairly high rates of survival. A seven year old wolf is considered to be pretty old, and a maximum lifespan is about 16 years.

Wolves communicate through facial expressions and body postures, scent-marking, growls, barks, whimpers and howls. Howling can mean many things: a greeting, a rallying cry to gather the pack together or to get ready for a hunt, an advertisement of their presence to warn other wolves away from their territory, spontaneous play and bonding. There is no evidence, however, that wolves howl at the moon. Pups begin to howl at one month old. The howl of the wolf can be heard for up to six miles. When wolves in a pack communicate with each other, they use their entire bodies: expressions of the eyes and mouth, set of the ears, tail, head, and hackles, and general body posture combine to express excitement, anxiety, aggression, or acquiescence. Wolves also wrestle, rub cheeks and noses, nip, nuzzle, and lick each other. Wolves also leave "messages" for themselves and each other by urinating, defecating, or scratching the ground to leave scent marks. These marks can set the boundaries of territories, record trails, warn off other wolves, or help lone wolves find unoccupied territory. No one knows how wolves get all this information from smelling scent marks, but it is likely that wolves are very good at distinguishing between many similar odors.

Wolves prey mainly on large hoofed mammals (known as ungulates) such as deer, elk, moose, caribou, bison, bighorn sheep and muskoxen. They also eat smaller prey such as snowshoe hare, beaver, rabbits, opossums and rodents. Although some wolves occasionally prey on livestock, wild prey are by far their preferred food source.

Wolves have several different methods of hunting, depending on the size of the prey. For little tidbits such as mice, an individual wolf will listen for the squeaking and rustling under the leaves, and then pounce with her front paws when she pinpoints the direction of the sound. They will also eat birds, especially when the birds are molting their feathers and cannot fly well. Individual wolves will also chase hares or follow beaver trails to try to catch the animal away from the water. When hunting deer, pack members frequently all participate in the locating and stalking of prey. After that, anywhere from one to all of the wolves will engage in the chase. Larger prey animals, such as moose, caribou, and elk, don't always run when they encounter a pack of wolves. If the prey animal stands its ground, the wolves will often approach cautiously or abandon their pursuit after a few moments. When a prey animal does flee, the pack of wolves will chase them. Most healthy ungulates are fast enough to outrun a pack of wolves. In fact, fewer than one out of ten attempts to chase moose actually end in a successful kill. If they start to fall behind, the pack will usually give up the chase. If the chosen prey is injured, weakened, or old, however, the wolves can usually catch up with them and attack. Contrary to many popular accounts, wolves rarely, if ever, engage in "hamstringing," or biting the tendons on the back of the leg. This practice is simply too dangerous for the wolf, because to bite the leg, the wolves risk getting kicked in the face by the animal's sharp hooves. Wolves tend to concentrate on the neck, shoulders, and sides instead.

Wolves' digestive systems operate somewhat differently than ours. They are adapted to process huge amounts of food at a time, then eat nothing for three days or more. Biologist David Mech witnessed a pack of 15 wolves kill a 600- pound moose and eat about half of it in an hour and a half, meat, bones, fur and all. This works out to about 20 pounds of food per wolf! Mech estimated that the wolves he witnessed in this encounter were about 85 pounds each, which means they each ate about 23% of their body weight. They don't do much chewing, mostly just tearing chunks off and swallowing them whole. After eating their fill, wolves will either spend a few hours relaxing and digesting, or return to the den to regurgitate food for the pups and other pack members who did not join in the hunt. A wolf's digestive system can handle a large amount of food quickly and efficiently, processing the meat and fat so thoroughly that only bones and fur are excreted in the scat.

Wolves began to take on their distinctively large size about 15 million years ago, and looked like they do today by about 1 million years ago. Every breed of dog that we have today, from poodles to huskies, are descended from a small subspecies of wolf that was domesticated in China about 12,000 to 15,000 years ago.

(The above information is from the Defenders of Wildlife's Wolf Pack Education Curriculum, available on their website at www.defenders.org)

The Grand Canyon Wolf Recovery Project is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization dedicated to bringing back wolves to help restore ecological health in the Grand Canyon region.

Help us bring back the wolves by becoming a monthly donor! Recurring donations help us plan for the future so we can schedule more educational programs and community events. Your donation will also provide us with the urgent resources we need to monitor more wolves in the wild and advocate for policies that allow wolves to roam freely.

Together, we can make a difference for wolves! Donations are 100% tax-deductible! Simply fill out the form and choose to make an automatic monthly, quarterly, annual, recurring, or one-time donation.

Monthly donors will receive our exclusive monthly newsletter called Lobo Howls, where we piece together lobo stories from the Lobo Family Tree Project!

Mail-in Donations are accepted here:

Grand Canyon Wolf Recovery Project

P.O. Box 233

Flagstaff, AZ 86002